Selling Our Rights - Homily on the Rich Young Ruler (2024)

When the future Elder, Arsenie Papacioc, was asked as a soldier in his 20s what he would do if he were a general to train soldiers, he replied, “I would teach them to die, if they didn’t fear death, they wouldn’t be so cowardly. They would fight better, and win”. “I would teach them to die”. This lesson from a soldier is pertinent for us today. It is no surprise that analogies between the spiritual life and physical combat are as old as Christianity itself. Just as courage in the face of death is necessary on the front line of war, so too, is it necessary for each one of us as we engage in spiritual warfare. And it’s this unwillingness to die that we see is the ultimate downfall of the rich man in today’s Gospel.

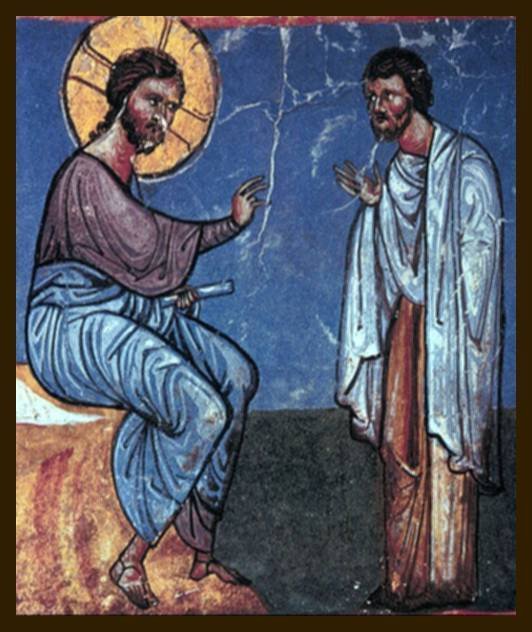

The rich ruler we read about today asked Life Himself what he must do in order to inherit eternal life. Christ reminds him of some of the commandments. Perhaps at this point the ruler is riding high, thinking about how correctly he has lived his life in following the Torah. To the ruler’s insistence that he has kept the commandments from his youth, Christ responds, “Yet lackest thou one thing: sell all that thou hast, and distribute unto the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come, follow me.” (Lk 18:22) But this is too much for our rich ruler. When faced with having to part from what is heart is most attached to—his wealth, he can’t bear the death that that would entail.

As elsewhere, Christ says, “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Mt. 6:21) and in today’s Gospel this is clearly manifested in the ruler. His treasure is his treasure. His treasure is all his wealth. His heart is in his large mansion, in his fine linens and luxurious clothes. His heart feeds on delicacies prepared by his servants every day. To sell all he has means nothing less for this man than to rip his heart out of his home, his clothes and finery, his jewelry, his large tracts of land. To give to the poor means this man has to give his heart to all those sick, unsightly and, in his mind, unworthy people. To follow Christ means this man has to die. He has to die to everything he has known and grown accustomed to. He has to die to all his attachments that he previously justified as perfectly pleasing to God—after all, he followed the commandments!

St. Sophrony laments, “It is impossible to live a Christian life, I can only die every day”. And thus we find that, like this rich ruler, we also must die. Every. Single. Day.

It can be tempting as monastics to think that we’ve already correctly responded to Christ’s summons to sell all we have and come and follow Him. It can be tempting for candidates and novices still in the honeymoon phase to think that the hard part of monasticism was in coming here. It can be equally tempting for those recently converted to think the hard part was being convinced of Orthodox dogma and getting used to fasting and long services. But Christ’s command to sell all we have and follow Him applies to each and every one of us. Every. Single. Day.

Giving up material goods is one thing, and it is difficult. But to give up our passions, to give up our sinful desires, to put to death the old man, how much more difficult. We have left the world and given everything up, except for our selves. We take our selves with all our passions wherever we go. We create the same mess for ourselves that we just got finished cleaning up elsewhere, or perhaps we didn’t even bother to do that and just fled amidst the turmoil we created. This is why Christ’s teaching today is so important for us, because if we do not learn to fight against our passions, if we are not brave enough to kill our old self, we will be miserable—I’m not even speaking about judgment and the next life, but that even in this life, living with the old self is inherently miserable. If we are too cowardly to put to death our passions, we will live the death-bearing life that this ruler also lived.

So how do we begin?

We need to learn how to “sell our rights”. Saints Barsanuphius and John often counsel monks that the reason they are upset with their brothers is because they have a “pretense to rights”. Namely, they think they are right during a conflict, they should have things their way, the other is wrong. A lot of the conflict that arises with others is simply because we don’t reproach ourselves for our contribution to the problem.

Just like the rich man counts his money at night with anxiety and excitement, reviewing all that he has, so we count up all the ways we’re right in disagreements with others. We tally up justifications for why things should be done the way we want them to, we go over in our heads why this is reasonable and we remind ourselves why our actions are good and correct.

Just as the rich man scrutinizes over every missing dime and is outraged over any penny he’s cheated out of, so too we scrutinize our brother in conflicts. We amass accusations against him for all the wrong, real or imaginary that he’s doing in a given situation. We go over the incident and review how un-monastic or un-Christian he was.

Why do we do this? In light of Elder Arsenie’s quote from the beginning, it is because we are cowards. We do not want to sell all and follow Christ. We do not want to sell the rights we think we have over our brothers. We do not want to sell our ego. It is much too precious to us. We’re afraid if we sell it, if we give our selves away, we will be left with nothing. Or worse than nothing, we will be left in the wrong. Without our egos, we will have nothing to hide behind. We will be left shown to be the poor sinners we are.

But while the Rich Man would have to spend at least a week, or perhaps a month or more selling all his goods and giving to the poor, we can sell all we have much more easily. With two words, we can sell all we have. By simply saying “forgive me”, we sell our egos, we sell our pretense to having rights over others. By saying “forgive me” we bravely kill the old man within us.

There are many ways we still have to sell everything and follow Christ. We have to sell the rights we think we have not only over our fellows, but also over the circumstances we encounter in our life. To follow Christ means to accept His providence over our life. It means we have to accept the circumstances we find ourselves in as given by or allowed by God. It means we have to stop complaining. To complain, to be ungrateful, is the exact opposite of the Christian life. We are called to be in communion with God. We call our greatest sacrament the Eucharist—thanksgiving. And to be ungrateful is literally to be un-eucharistic.

The fathers tell us that it is not enough to say we are sinners. To find out if we really believe in our hearts if we consider ourselves to be sinners, we have to see how we respond to the crosses God allows us to have. Every night we say the prayer of St. John Damascene before sleep. In this prayer we read : “I know that I am unworthy of Thy love for mankind and am worthy of every condemnation and torment”. And then we go to sleep, and the next day we’re confronted with problems and trials and crises. Now if we say that we are sinners, how can we complain about anything that might happen to us that is less than “every condemnation and torment”? When confronted with illnesses, loss of respect, slander, having to bear our brother’s burdens, missed opportunities, change of obediences, change of how we do things, repeated failures at work or in our relations with others, if we meet them with grumbling and complaining, we are saying we don’t really believe we are sinners. That doesn’t mean we have to pretend that the crosses we have to bear aren’t grievous and painful. We don’t have to pretend that everything we encounter is easy or simple. But if we constantly complain about our lot and what befalls us, it means we don’t think our misdeeds exist or if they do, they don’t warrant any minor correction or deserve any affliction whatsoever. It means we haven’t sold our egos. It means we still want to maintain our rights over our life. We still want to think that we should have things our way. It means we don’t trust God or accept His providence in our life.

There’s a wonderful story in the Gulag Archipelago about a woman, Dusya Chmil, who was sentenced as a political offender and sent to the gulags. As a reminder, the gulags were the expansive prison and death camps that slaughtered millions of people over the course of 4 decades in the Soviet Union. To be charged with a political offense more or less meant the person was innocent. It meant they crossed themselves in front of the wrong person. It meant they made a joke about Stalin or some lesser party official. It meant some stranger they only briefly met the other day blurted out their name under interrogation to the secret police just to get them off his own back. This was the majority of those sent to the gulags. Solzhenitsyn writes about the psychological shock that prisoners go through upon being charged, being interrogated, and being shipped off because of how outrageously absurd it was. No longer could the person charged ignore that he lived in an insane society governed by demonic laws. How can this happen? Why me? There must have been some mistake! What will my family do? How will they survive? Fear, anger, denial, confusion. Most political sentences were at least 10 years, some up to 25. For many despair and bitterness sank in. How did Dusya respond?

Upon Dusya’s entrance at her prison camp she was asked by the guards:

“Chmil!... What’s your term?”

And she gently, good-naturedly replied: “Why are you asking, my boy? It’s all written down there. I can’t remember them all.” (She had a bouquet of sections under Article 58.) “Your term!”

Auntie Dusya sighed. She wasn’t giving such contradictory answers in order to annoy the convoy. In her own simplehearted way she pondered this question: Her term? Did they really think it was given to human beings to know their terms? “What term! … Till God forgives my sins—till then I’ll be serving time.” “You are a silly, you! A silly!” The convoy guards laughed. “Fifteen years you’ve got, and you’ll serve them all, and maybe some more besides.” But after two and a half years of her term had passed, even though she had sent no petitions—all of a sudden a piece of paper came: release! (Gulag Archipelago Vol. 2 p. 624).

Dusya had already sold everything and followed after Christ. She sold her “rights”, she sold any sense that this wasn’t fair and that she was being mistreated. She let go of any sense that she didn’t deserve this. Instead, she continued her life of repentance. There was no reason given for Dusya’s release. But she knew the reason—her repentance was accepted (and probably crowned as well). And God did not just release her for the sake of her long-suffering, but so that we can learn from her. So that we can see that even in the depths of the hell that was the Soviet Union, God’s love and concern for His children is all-powerful, but especially for those who sold everything for His sake.

On hearing how difficult it is for a rich man to be saved, the Apostles asked, “Who then can be saved?” and our Merciful Savior does not hesitate to respond, “The things which are impossible with men are possible with God”. Beloved, may we also learn to sell our rights. May we also learn to say forgive me, even when we’re “right”. May we learn to stop complaining and begin to see God’s hand in the events of our life, namely, His earnest desire for our repentance and His loving care for us. Amen.

Leave a comment