The Cross and the Wedding Garment - Homily for the 14th Sunday after Pentecost (2024)

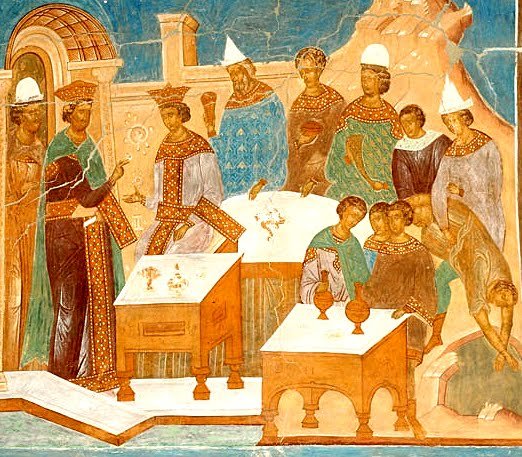

What is the essence of Orthodoxy? Orthodoxy has a lot of rituals. Rituals are important but the essence is not about rituals. Orthodoxy has a lot of rules—liturgical rules, fasting rules, prayer rules. The rules are important, but the essence is not in rules. Orthodoxy has a lot of theology—dogmatic, ascetical, mystical. Theology is important, but the essence is not theology. Orthodoxy is about that great mystery that our forefather Adam prophesied at the beginning. When God brought Eve to Adam after He fashioned her from his rib, Adam said, “Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh” (Gen. 2:24). The essence of Orthodoxy is this prophesy. Referring to this, St. Paul writes to the Ephesians that while human marriage “is a great mystery” it points to an even greater one: “but I speak concerning Christ and the church” (Eph. 5:32). The essence of Orthodoxy is that Christ should leave His Father in heaven, not by a change of place, but by becoming man. And that He should cleave to His bride—the Church, and they shall be one. God is love and His love is so superabundant that He desires to pour it, or rather, Himself, upon on all creation; to have such creatures as us humans to respond to and receive this love and to partake of the unending life of the Trinity. The essence of Orthodoxy is the Wedding Banquet of the King’s Son that we hear in today’s Gospel.

If this is so, we can see how terrible it is to reject the King’s invitation, preferring things of this life as the first guests did. We can also see how spiritually disastrous it is to accept the invitation only to arrive unprepared, improperly dressed. Today I want to examine “What is this wedding garment that the guest did not wear?”

According to St. Augustine, the garment God requires us to bring to the wedding is love. St. Paul reminds us that it doesn’t matter what spiritual gifts we have, what great deeds we perform—even martyrdom! for if we do not have love, these things profit us nothing. How often do we need to be reminded of this painful truth! It doesn’t matter how long we’ve been Orthodox or been at this monastery. It doesn’t matter what our ascetic practices are, how successful our projects and tasks and obediences are. None of these matter if we don’t actually love the people God places in our life. If we don’t love our brother, we, too, will appear at the wedding feast naked and speechless before the Bridegroom.

If the wedding garment that we must have is love, what is that love? Archimandrite Vasileos, a disciple of St. Paisios, writes that “Love is sacrifice, not sentimentality”. Love is sacrifice. It’s not the intense emotional feelings one might get when they first meet someone new. It’s not the fiery zeal a new convert or a novice when they just begin the spiritual life. It is sacrifice. And providentially today, if I may be so bold, we have in front of us the garment of love that Christ wears—His precious Cross. What greater love could God possibly show us than what He shows us this week as the Cross is displayed for all to see and to bow down and kiss? Is not the Cross the Bridegroom’s pledge of His eternal and boundless love for us? Is this not the sign that love is sacrifice, that love denies itself?

How do we put on this garment of love? By our sacrifices. Not just great sacrifices like putting off a career for years to support family members, rescuing people out of a burning building, raising millions of dollars for the homeless. We rarely, if ever, have opportunities to do these great deeds. More importantly, our sacrifice is what we can offer our brother and our neighbor every day, the small, unnoticed sacrifices of our attention and care.

God will not require of us the sacrifices of the early Christians—their asceticism (even amongst lay people), their trials and torments they went through. He knows that we’re more or less spiritually handicapped. This is not an excuse not to bother, but to have a better understanding of what we can do.

Fr. John Parker of St. Tikhon’s Seminary gives the following advice to catechumens. He tells them to read the New Testament every day. And when you see the trash is full, take the trash out. And when you see the trash is full again, take the trash out again. Even if nobody’s helping you. Even if it seems nobody else is doing it. And every time you see the trash is full, keep taking the trash out until you stop caring that nobody is helping you and nobody else seems to be doing it. And then maybe you can begin to live the spiritual life. According to Fr. John’s definition, how many of us have actually begun the spiritual life?

There’s a lot to unpack here. First, we have to actually be paying attention to our environment and the people in it. Our ADHD, smartphone, smart watch, 24/7 social media news world makes it particularly hard to pay attention to things outside of our immediate anxious concerns and distractions. This isn’t just about trash, we have to actually pay attention to our brothers, to our family members, to our co-workers. Not as busybodies or witch-hunters, but in a loving and attentive way. Do we even notice that our brother is quieter than usual and seems that perhaps he’s having some temptations and we should perhaps cheer him up or at least pray for him? Or are we so busy stewing in our own problems that we can’t see? Ross Douthout, in his memoirs recounting his struggle with chronic Lyme disease, writes, “We filter for people who are like us—we also filter for misery, so that suffering around us passes unheard and unseen”. If we can’t see the struggle and pain the people around us are in, how can we love them? If we can’t love the people we encounter every day, how will we ever love strangers or our enemies? We have to learn how to see.

Second, if we’re aware of a problem that we can take care of, do we actually do something about it? Once we learn to see something—a full trash can, a task left undone by an overburdened family member or co-worker, we will see these things more often and we can respond better. Taking the trash out, washing dishes, cleaning toilets, putting the chairs back in order, covering up the small mistakes someone else left behind. All these simple obvious tasks are ways of sacrificing our time and showing our love. And this is what God is usually calling us to do almost all the time if we have eyes to see. Fr. John Krestiankin writes, “We long to do great works, because minor good deeds do not feed our pride, for they go unnoticed, are hidden, and are salvific precisely for that reason”. (May God Give You Wisdom, p. 352). How do we imagine that we’ll rise to the challenge of enduring persecution and slander, of loving those who hate us, when we can’t give five minutes for a tired brother, when we can’t clean up someone else’s mess? Love starts in small things.

Third, what Fr. John Parker says is key, “keep taking the trash out until you stop caring that no one else is doing it”. That requires us to sacrifice our martyr’s complex, our exalted view of ourselves and what we do. If we’ve ever had the thought, “If it weren’t for me, nobody would do x,” or “Once I’m gone, then they’ll realize how much I did”—it’s a good sign we have a martyr’s complex. It’s so self-pitying and narrow-minded, as if only the tasks we do are the ones that are necessary for the upkeep of our family, or of the monastery, or of our parish or place of work. Our capacity is fairly limited and if we think we’re taking the lion’s share of work, we probably think this because we enjoy staring at the load on our shoulders more than the observing the burdens others are carrying. It’s the saints among us who bear us up, regardless of what tasks they may or may not be doing. Even if we think they’re doing nothing at all. And they certainly don’t believe in their own significance, but rather remember Christ’s words, “When ye shall have done all those things which are commanded you, say, ‘We are unprofitable servants: we have done that which was our duty to do’” (Luke 17:10). And yet, these unprofitable servants are the ones who love God and us the most. In their prayers and their humility, they are the ones who cooperate with God and weave for themselves the shining wedding garment that they will present themselves in on that day.

Beloved, our whole life is Christ calling us to Himself, bidding us to come to the wedding feast. Christ clothes Himself in the Cross, the raiment of His love for us, and we, too, must clothe ourselves in our wedding garment. We must put on works of love, the sacrifices of our time and attention for the people in front of us. God invites us to the wedding feast each day at the Divine Liturgy. It’s this wedding feast that prepares us for that one—or rather, they are one and the same. The grace that we receive in the liturgy is what enables us to do what Christ commands. We can’t pay attention to our environment, to our brothers, to our family, to our co-workers with just force of will alone. We can’t properly respond to them with just the force of will alone. We can’t even do good deeds without complaining with just the force of will alone. We need God’s grace for everything. And He graciously provides, if only we hearken unto Him Who said, “Behold, I have prepared my dinner: my oxen and my fatlings are killed, and all things are ready: come unto the marriage” Amen.

Leave a comment